Here Annie is seated in a row with William Rainey Harper (first president of the university and a force of nature on the right) and John D. Rockefeller (wealthiest man in America in the top hat). I love the expression of enduring all the speechifying but also, I think, pleasure that she had reached this day. She’d faced down Harper and gotten what she wanted.

By 1889, she was the last of her close family. Her beloved Charles was gone. She kept up her interests in the Fortnightly Club and the Chicago Woman’s Club and supporting the settlement house—saying they kept her from being so lonesome--but she was very aware that she was the “keeper of the mementos,” not just of her family but of a lost Chicago. The city had 4,000 people when she was born. It was over a million in 1890 and doubling every decade. Development surrounded her home, which was no longer a rural oasis, especially after selling off the farmland to support herself. The World’s Fair was about to transform the neighborhood and city.

One change grabbed her attention and the attention of the Chicago Woman’s Club--the plans for a coeducational university in Hyde Park, where women would have the same coursework, tuition, and degree as the men. The university talks about the individual donors, but the Tribune at the time pointed to the organizing efforts of the Chicago Woman’s Club: ”To the Chicago Woman’s Club is due much credit for the favorable outcome of the plans for women’s dormitories. There had been a movement on foot for some time looking to the building of one or more halls, but with no material success until a meeting of the Womans’ Club was held in the spring of [1892]. Dr. Harper appeared before the club and spoke regarding the plans he had hoped to carry out.”

By 1899, Annie had a plan for how to insure that Charles and her father would be remembered. She would donate her share of the real estate that Charles had bought back in the 1860s on the edge of the city to finance the construction of a men’s dorm. That real estate is now One North LaSalle, worth $200,000 in 1899 (about $6 million today). Worth a heck of a lot more now!

The architect she wanted was Dwight Heald Perkins. Perkins was the son of Annie’s childhood friend, Marion Perkins, whose husband had died early. Dwight had dropped out of high school to support the family and happened to get a job as an errand boy for an architectural firm and discovered his calling. Annie paid his tuition and expenses to the architectural school at MIT. He was so talented, he graduated early for a job with Burnham and Root, whose office had expanded in the build-up to the Columbian Exposition. After the fair, he started his own firm.

In 1898, a number of paths crossed. Jenkins Lloyd Jones was the Unitarian minister who sponsored the settlement house that Annie supported. Jones wanted to build a modern building to house a complex of services called the Abraham Lincoln Center. Jones hired his nephew—Frank Lloyd Wright. When Jones found that Wright was hard to work with, he brought in Perkins, who was also devoted to the Prairie School of architecture, to work with Wright. I like to imagine Annie confronting the very young Frank Lloyd Wright.

Now, in 1899, Annie wanted Dwight to design her Charles Hitchcock Hall. So she wrote to the University of Chicago.

First, Harper and the male trustees tried to convince her to just donate money so they could match a grant from Rockefeller. Annie said no—it’s a dorm named for Charles.

Then Harper and the trustees insisted that the architect had to be their standard neo-Gothic one, Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge. Annie wrote back (quoting Susan O’Connor Davis book) “I am not content that the building should be put up as my expression of an adequate memorial to my husband, and as my ideal of what a boy’s dormitory should be, when I have not been consulted at all.”

Harper decided that they would humor her, pretending to consult Dwight, while having the real plans drawn up by their architect. When Annie found out, she rewrote the contract, spelling out her role in approving the plans. In 1900, she sailed to Europe with Dwight and his wife, who had joined the Fortnightly Club, to get ideas.

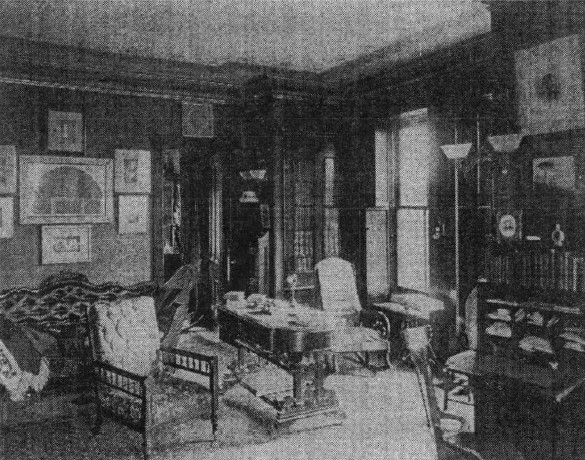

The exterior of Hitchcock Hall blends with the neo-Gothic theme of the Quads, but the interior was Prairie School. It included a room with the furniture that her parents had brought to Illinois on the Erie Canal and a library with Charles’s books. Annie wrote, “The great satisfaction with anything I place in Hitchcock Hall is that the Trustees promise me it shall remain forever a part of the Memorial." Unfortunately, she apparently didn’t put that in the contract. It’s not clear that anything other than the building survives.

In 1901, she laid the cornerstone. In 1902, when everything was done to her satisfaction, she hosted a party for all of the laborers and craftsmen who worked on it to thank them for building Charles Hitchcock Hall. I think she’d like knowing that it’s on the National Register of Historic Places.

.jpg?part=0.1&view=1)